How Long Does Therapy Take?

The ultimate question on how therapy works often remains unanswered. How long do people need to be in therapy? Let's talk about whether people ever do let go of their troubles, and how we can see it.

BUT HOW?

How long until therapy "works"?

I wish I knew. Therapists often note the tendency for analytical, results-driven, aka techie clients, like me to expect immediate results from therapy. However, therapy can not "fix" anybody. One hour a week is not enough to change your life without practicing and applying what you've learned. The rate of co-occurring challenges is also so high, it's rare that a client starts therapy with only one clear-cut goal. Each of these factors (and more) influence the length and effectiveness of therapy.

Yet the question remains.

“When is it time to graduate from therapy? ”

People often fear becoming dependent on the luxury of a supportive "crutch". We are resilient, strong, and independent, right? We can figure this out ourselves. We can move on and get over it on our own. And some lucky ones do.

People heal in different ways.

Many have never tried therapy, while others feel they're set after one session. Some dive in for a few months, while many others have been in and out of therapy for years.

When clients have stayed with their therapist for years, clinicians often interpret this alliance as an underlying affirmation of their skills. However, could a client continuing therapy for years potentially reflect a lack of progress? (Alpert, 2012) Or does the extensive length of therapy reflect the complexities of the clients' traumas?

The benefits of therapy come after some tough discussions. People do not typically enjoy thinking about what they discuss in therapy, let alone often talk about these things with others. However, some people find that therapy can help release the burdens they have been carrying internally.

One Buddhist sentiment attributes great suffering to craving and clinging. The complexities of mental health can feel both physically and psychologically heavy. When applied to what some carry with them, therapy can help people gradually let go of some of this weight. Relatedly, the book "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner" describes an albatross hanging around a troubled man's neck.

LET THIS ALBATROSS GO

Nobody says it is easy to learn to manage this weight. One guided meditation, for example, considers it an ongoing practice, and suggests repeating "let go, let go, let go" to yourself in difficult circumstances.

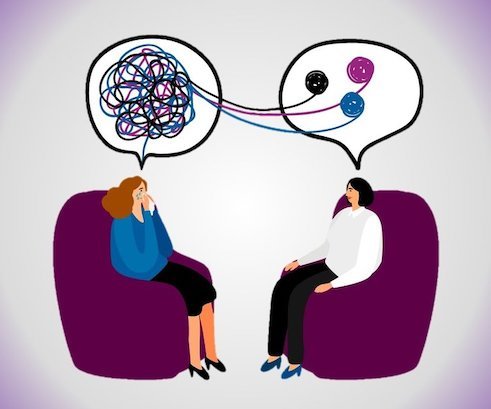

UNTANGLING IT ALL TOGETHER IN THERAPY

Growing a support system outside of therapy

While therapy can help unravel things that get stuck in people's minds, an ultimate goal is for people to develop additional support systems in their community. The experience of a strong therapeutic alliance can ideally translate to other relationships. Therapists often help clients identify other people who feel safe and supportive and respect healthy boundaries. Establishing alternative social supports can then significantly improve people's health and well-being.

THE BEAUTY OF SOCIAL SUPPORT

How do you know therapy "worked"?

For many analytical people like me, results feel more definitive when represented quantitatively. Surely, people with Depression, for example, can have a gut feeling regarding their improved mood, reduction in negative self-talk, and increased enjoyment of activities. However, seeing a chart graphing evidence-based results can be even more gratifying.

Clinical Case Evaluation has been one of my favorite classes in Columbia's Masters in Social Work program. Although evidence-based practice has become a buzz word in the clinical field, the term also refers to a more specific approach to clinical work.

Tracking client outcomes through evidence-based assessment measures provides a way to comprehensively understand and track how mental health challenges are responding to clinical interventions. Realistically, people may feel worse throughout the course of therapy; crises happen and mental health challenges can be unpredictable. Some people's conditions can also be treatment-resistant and require new approaches. Without valid and reliable evidence-based measures, the clinician remains biased towards assuming therapy is working. Clients often want to please their clinician and report improvements along the way, while downplaying the continued impacts of their symptoms. Relatedly, clinicians often overestimate the effectiveness of their interventions (Elks & Kirkhart, 1993).

However, many therapists do not use measures in their clinical practice (Shlonsky & Gibbs, 2004). Two of the most cited reasons include not receiving training on how to implement clinical measures in practice and not having the time to do so given their intensive caseloads. Additionally, in my experience so far, some clients were eager to have ongoing assessment questionnaires integrated into our therapy work. Others reported it felt like a test or felt less comfortable with reading and writing. I also wondered whether some had trouble saying no when I asked.

For those clients who seemed interested though, I prepared charts similar to the one below and we’re able to celebrate their objective progress together. One day, I plan to frame a chart like this in my therapy office.

MY THERAPY CLIENT’S RESOLUTION OF MODERATE DEPRESSIVE AND ANXIOUS SYMPTOMS WITHIN 3 MONTHS

What you are seeing here are evidence-based assessments of one client's significant reduction in symptoms of Depression and Anxiety throughout the course of therapy with me. Although many do not discuss the benefits of therapy openly or in great detail, there can be a strong sense of accomplishment in realizing your personal growth. Imagine how differently the client on the other side of this chart felt in three months. However, this data only shows what is being tracked: Depression and Anxiety. If this client was also dealing with an eating disorder, for example, this graph would not be telling the whole story. As I mentioned, people often have a variety of co-occurring challenges. And yet, especially after some time in therapy, it is important to celebrate personal progress and whatever helped people get there.

“Therapy is oftentimes just one small piece of one’s larger mission of self-improvement. ”

At some point, you expand your set of tools for approaching your life, career, and relationships. Gradually, life becomes a little easier. There is a core tension though between clients resuming life without therapy and the clinician's perspective. Also, the client's sense of readiness to stop therapy does not always match the therapist's. Therapy can feel like peeling an onion, whereafter one layer reveals another. Although breaking up with your therapist is not easy, when is it time to stop peeling? Or maybe choosing to pause therapy is more so the decision? As with most good-byes, ideally therapy ends on good terms and the door remains open for reconnecting down the line.

What we do know is that therapy works. At some point, people are able to let go and reach their personal goals. However long it takes though may depend on you.

I wish there was a concrete formula to calculate the ideal length of therapy for each person. What I will say is that you have the right to finish therapy whenever you feel ready. As you do some self-reflection before deciding, the following questions may be helpful to consider:

What were your initial treatment goals?

How do you know therapy has been "working" for you?

How confident are you in your therapist's ability to help you?

Would you rather find a new therapist?

How stable has your mood and life been recently?

Other sources of social support you can turn to?

Comfortable with tolerating distress, practicing coping skills, and self-care?

What would your loved ones, therapist, doctor, and/or psychiatrist think about you pausing therapy?

Thank you for reading. If you'd like to talk about anything, you're welcome to reach me at lisa@letstalkaboutanything.com or book a complimentary consult call

Warmly,

Lisa Abdilova Andresen

--

Works Referenced:

Alpert, J. (2012, April 21). In Therapy Forever? Enough Already. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/22/opinion/sunday/in-therapy-forever-enough-already.html

Elks, M. A., & Kirkhart, K. E. (1993). Evaluating Effectiveness from the Practitioner Perspective. Social Work, 38(5), 554–563.

Shlonsky, A., & Gibbs, L. (2004). Will the Real Evidence-Based Practice Please Stand Up? Teaching the Process of Evidence-Based Practice to the Helping Professions. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 4(2), 137–153. https://doi.org/10.1093/brief-treatment/mhh011